Adaptive therapy shows promise in fighting drug-resistant cancer

BRUSSELS, Belgium – New research published in the journal Cancer Research provides evidence that adaptive therapy represents a promising strategy to address one of oncology's significant challenges: drug resistance. Anticancer Fund is supporting clinical trials that explore this treatment approach, which offers a different perspective on how to treat cancer.

A different approach to treating cancer

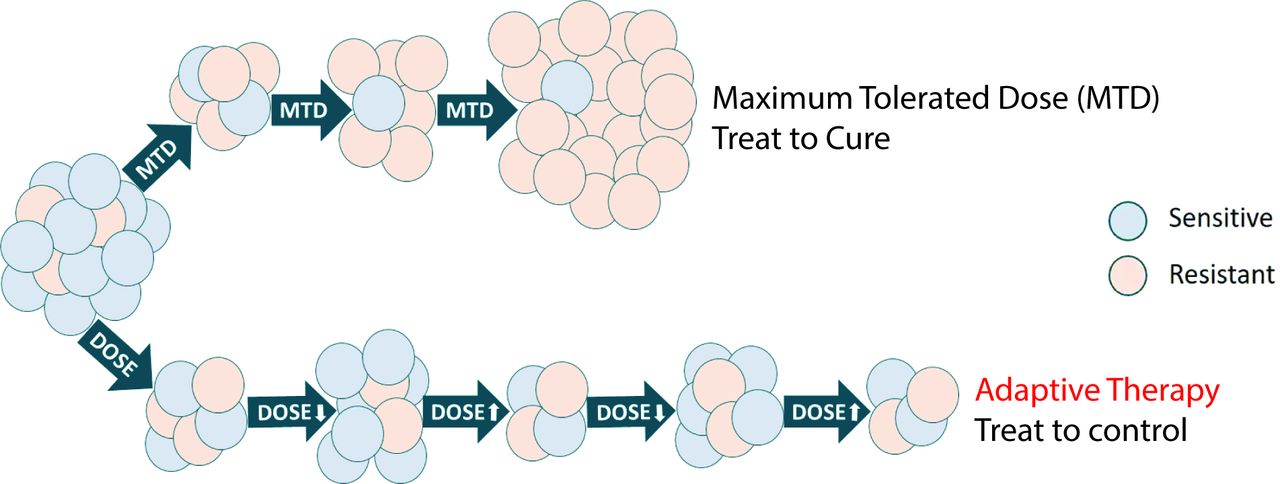

For years, cancer treatment has followed a seemingly logical approach: deliver the highest possible dose of chemotherapy to eliminate as many cancer cells as possible. However, this strategy often backfires. While initially effective, high-dose treatments create intense selective pressure that favours the survival of drug-resistant cancer cells. Over time, these resistant cells multiply and dominate, leading to treatment failure and disease progression.

Adaptive therapy offers an alternative approach. Instead of treating cancer as an enemy to be destroyed at all costs, this strategy manages cancer more like a chronic condition. Rather than administering fixed, maximum doses, adaptive therapy adjusts drug dosing based on tumour response, maintaining a delicate balance between drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cells.

The underlying principle is both simple and scientifically sophisticated: drug-sensitive cancer cells are generally more robust and competitive than their resistant counterparts when no treatment pressure is present. By maintaining a population of sensitive cells, we can use them as natural competitors to suppress the growth of resistant cells, potentially controlling the cancer for longer periods while reducing toxicity.

Research foundation and scientific evidence

The scientific foundation for adaptive therapy has been strengthened by research led by Professor Michelle Lockley at Queen Mary University of London and her team at the Centre for Cancer Evolution at Barts Cancer Institute. Their comprehensive study, recently published in Cancer Research, demonstrates the potential of this approach in ovarian cancer treatment.

The research team conducted extensive laboratory tests using ovarian cancer cells, both sensitive and resistant, under normal and low-resource conditions that mimic the challenging environment inside a tumour. Their findings revealed that resistant cells grew slower and died more frequently when competing with sensitive cells in resource-limited settings, demonstrating that they are less "fit."

Researchers tested adaptive therapy in mice with ovarian cancer. The conclusion? Mice receiving adaptive therapy lived longer than those on standard treatment, and had less side effects.

Anticancer Fund is supporting two clinical trials testing adaptive therapy: the ANZadapt trial for patients with metastatic prostate cancer and the ACTOv trial for patients with advanced ovarian cancer.

The ACTOv clinical trial

Building on these preclinical results, Anticancer Fund is supporting the ACTOv clinical trial for patients with advanced ovarian cancer in the UK. This trial translates laboratory discoveries into potential patient benefits.

The ACTOv trial specifically targets patients with relapsed ovarian cancer, using carboplatin doses adjusted based on CA125 levels – a blood test commonly used to monitor ovarian cancer patients. This approach allows for real-time adaptation of treatment based on tumour response.

Looking forward

This research represents more than just a new treatment approach – it embodies a different philosophy of cancer care that prioritises long-term disease control and quality of life alongside survival outcomes. As clinical trials like ACTOv continue to generate data, the cancer community watches with anticipation for results that could improve the future of cancer treatment.

Interview with Professor Michelle Lockley

Let’s dive into science behind the ACTOv trial and ask some questions to the pioneer of adaptive therapy, Professor Michelle Lockley. She’s a Professor of Medical Oncology and Group Leader at the Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London, and a Consultant Medical Oncologist. She specialises in the systemic treatment of gynaecological cancers, with particular expertise in ovarian cancer and clinical trials, including rare ovarian cancer sub-types.

The Aha-moment: what was the moment that made you think 'we should treat cancer differently' and led you to adaptive therapy research?

"I first heard about adaptive therapy in a talk given by Professor Trevor Graham. I was interested in drug resistance and strategies to overcome it, because I see it play out in clinic every week. We give patients with ovarian cancer platinum containing chemotherapy and we know that it works less well each time we give it. I had long thought that the drugs were influencing the development of resistance. And that, if we could stretch out the time between treatments and preserve platinum sensitivity for longer, that would be a big win. Adaptive therapy just really chimed with me."

How do you explain to patients willing to be cured as soon as possible, that getting 'less' chemotherapy might help them more? What's their reaction to this counterintuitive approach?

"Our adaptive therapy trial, ACTOv is only recruiting patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. These women are already accustomed to having chemotherapy with the associated toxicities and they have experienced their disease coming back. They already had honest conversations with their oncologists about their future and will know that their cancer is incurable and the goal is to keep them as well as we can for as long as we can. In that context, I find that patients are very open to the idea that we are going to try something new and that we may be able to achieve better control of their cancer with lower drug doses and fewer side effects."

ACTOv focuses on ovarian cancer, but where do you see adaptive therapy having the biggest impact? Are there cancer types where this approach might work better, or won't work?

"ACTOv is using carboplatin, which is an intravenous drug. I think that adaptive therapy might be easier all round with oral or tablet treatments. Also, in ACTOv, we are basing carboplatin doses on changes in CA125, which is a blood test we commonly use when we are treating ovarian cancer patients. This means that ACTOv is adapting doses based on a blood test that indicates the amount of cancer someone has. We think that adaptive therapy will work best when it is based on the amount of treatment resistant cancer there is, rather than the total amount of cancer. It's not all that easy to measure that but we are working out new ways to do this in ovarian cancer and we can already measure resistance for some of the newer targeted therapies. So, I would say that I am most optimistic about adaptive therapy being beneficial in those cancers that have an effective, targeted, tablet treatment with well understood resistant mechanisms and a good blood test that can measure the emergence of resistance."

Adaptive therapy requires long-term follow-up and dose adjustments. Could this work out in everyday oncology practice, or would changes be needed in how care is delivered?

"That is actually working well in ACTOv. All we are changing is the drug dose, all other aspects of care remain the same and we have not had issues with delivery of treatment so far. There could be challenges in implementing new biomarkers into clinical practice, particularly if a quick turnaround time is needed to determine adaptive therapy. New drugs often need new biomarkers, PARPi and Mirvetuxumab in ovarian cancer for example, and these are now used routinely around the world."

A more general question: in what oncology field do you expect to see the major breakthroughs in the next decade?

"I know most about ovarian cancer and antibody drug conjugates are the big news at the moment. It would be great if we could find a way to improve immunotherapy for ovarian cancer patients – it would be nice to think that is achievable in 10 years."

Further reading

Publication

About ACTOv

- ACTOv is a clinical trial supported by the Anticancer Fund, open to patients with advanced ovarian cancer in the UK, led by Dr. Michelle Lockley at Queen Mary University of London.

- Study protocol of the trial

Blog

Determining the optimal use of approved drugs is an innovative way to improve existing treatments.